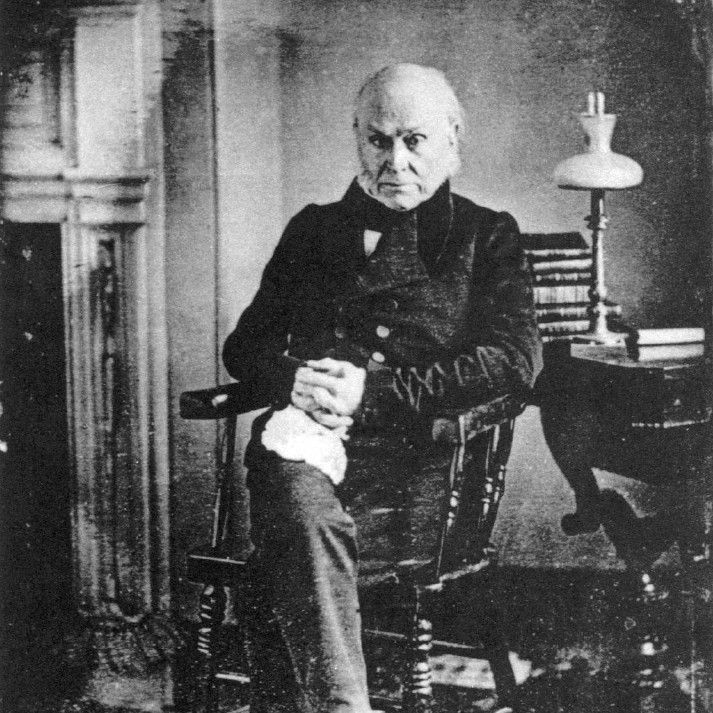

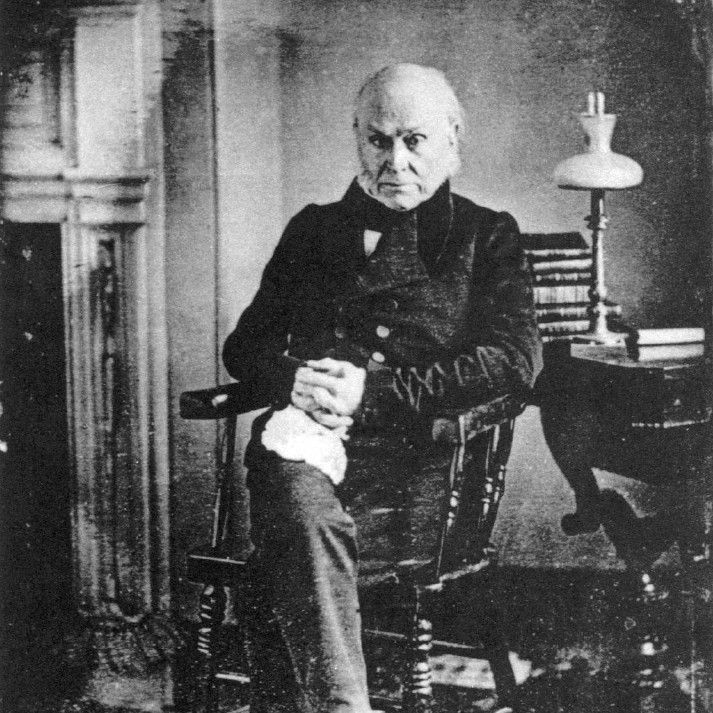

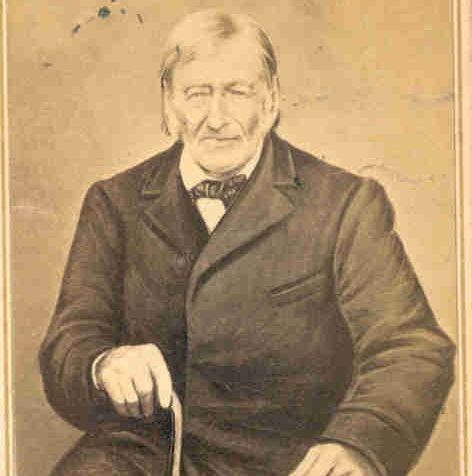

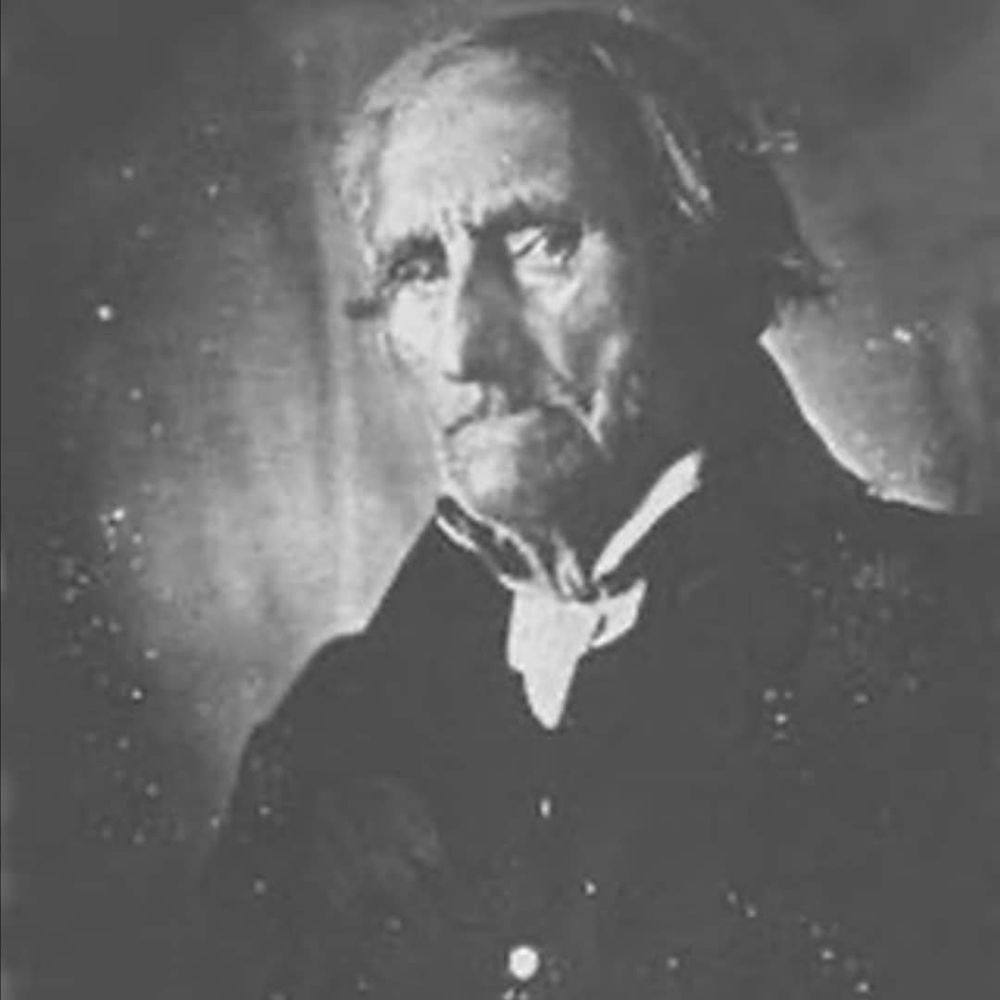

Only a handful of Americans born before 1750 had their likenesses captured by the new medium of photography, which came to America in 1839. The precise date of Stone’s birth is uncertain. The inscription in this case gives it as 1744, while his obituary gives the year 1743. Stone’s pension application of 1820 states that he was then sixty-six, suggesting a birth year of 1754. The Copes-Bissett family Bible, which records the family of Stone’s presumed daughter Hannah, gives the year 1747.

In any event, Baltus Stone is one of the very earliest-born people to be photographed. The earliest competitor we have seen cited is a John Adams born in Worcester in 1745. Maureen Taylor’s The Last Muster: Images of The Revolutionary War Generation (2010) reproduces portraits of only two men born as early as that decade, in 1746 and circa 1749. Another candidate is the African-American slave Caesar, with an uncorroborated birth year of 1737, whose daguerreotype is in the collection of The New-York Historical Society.

Stone died just months after sitting for this daguerreotype. His October 1846 obituary states: ‘The venerable Baltis [sic] Stone, well known in Southward [presumably Southwark, South Philadelphia] as the oldest inhabitant, & a veteran of Revolutionary times, died on Thu. Last. At an early age the dec’d entered the army as a rifleman, along with his father, who sealed his devotion for his adopted country with his life’s blood. Baltis Stone was with Washington in every campaign of the Revolutionary struggle, & witnessed the battles of Bunker Hill, Trenton, Germantown, Red Bank, & others, & yet escaped without receiving a wound. He has received a pension from Gov’t, as a reward for these services, for many years. He was 103 years & 16 days old at his death. He was able to walk, supported by his staff, until within a few months past” (National Intelligencer, 27 October 1846).

Stone’s official pension file reveals the obituary’s embellishments. According to that file, Stone enlisted as a private in the Pennsylvania Rifle Regiment. He saw action in the Battle of Long Island (August 1776). Captured by the British, he was freed in an exchange at the end of his enlistment period. By late 1777 Stone had reenlisted as a wagoner—possibly with Philadelphia’s First Battalion, City Militia—and subsequently saw action at Brandywine (September 1777) and Germantown (October 1777). Stone first applied for a veteran’s pension in June 1818, after the passage of the Act to Provide for Certain Persons Engaged in the Land and Naval Service of the United States in the Revolutionary War. Stone was apparently required to reapply for his $8 per month pension in 1820, as the file also contains a deposition from that year. Stone declared at that time, “I have no property of any description, am by occupation a day labourer, but from decrepitude and general infirmity am unable to labour. I have one daughter married with whom I reside and I am in such indigent circumstances as to be unable to support myself without the assistance of my country.”

This tremendous daguerreotype of an ancient Revolutionary War veteran virtually transports us to another era in the nation’s history, before the United States of America even existed.

Any damn fool can navigate the world sober. It takes a really good sailor to do it drunk